When Everyone Loses: Understanding Why Wars Start and How They End

Wars are horrible and costly. They devastate economies and communities, upending lives and leaving trauma and destruction in their wake. So why do we fight them?

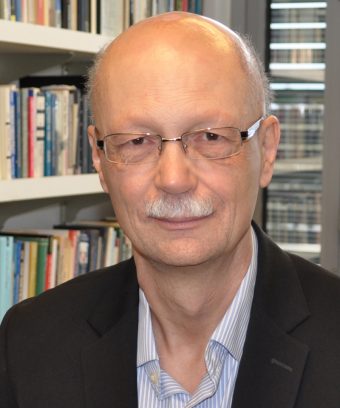

On this episode of Talking Policy, host Lindsay Shingler is joined by UC San Diego distinguished professor and IGCC senior fellow David Lake, who shares a new theory about war that views them as less about “winning” and more as evidence of failure—an event in which everyone loses relative to agreements and compromises that might have been reached without fighting. In an era of growing global uncertainty; protracted wars in Europe, Africa, and beyond; and the threat of new wars, this new way of thinking may provide fresh clues about how to prevent conflicts from starting in the first place.

This interview was conducted on February 12, 2025. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity. Subscribe to Talking Policy on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Captivate, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Lindsay: Why did Russia invade Ukraine? What’s driving civil war in Sudan? Will China invade Taiwan? Is there a risk of civil war in the United States? War and violence are dark and recurring features of human history. Because they bring such devastation, it’s critical to understand why they happen, and what we can do about them.

On this episode of Talking Policy, I’m joined by David Lake, one of the world’s foremost scholars of international relations, and a distinguished professor at UC San Diego and senior fellow at IGCC. David and I will talk about a new theory about what drives countries to war, and what this new way of thinking can tell us about how wars can end.

David, thanks for being with us on Talking Policy.

David: My pleasure.

Lindsay: Okay, so we all know that war and other forms of political violence are bad, although most of us have never been near a war or experienced their effects directly. Your work focuses on understanding why they happen [and] how they can be prevented. To start, can you set the scene for us? Remind us what happens in wars; what makes them so bad?

David: What makes war bad is the human casualty, that we now understand is in many ways needless, right? Once upon a time, we thought wars had a purpose. Now we tend to think of them as being mistakes that could be prevented in some deep way. And so the casualties are astounding in some ways, right?

We don’t have a consensus definition of what a war is. Sometimes they’re counted, you have to have a thousand people die per year, sometimes it’s 25. Different institutes collect data in different ways, right? But our best guess now is probably 50 to 60 wars underway this year. And, you know, the news focuses on Ukraine and Gaza. If you pick up the newspaper, that’s all you see these days. But by far, most conflicts are in Africa, as they’re unfolding in the world today.

And the casualties in war can be enormous. We think of the mega wars, right? World War II was 21 to 30 million people were killed. World War I was 7 to 9 million. Vietnam, about 1 million. Those are large wars and pretty significant casualty rates? Most wars are smaller than that, but still pretty significant. Alright, so the Persian Gulf War was 20,000 to 40,000 killed. Iraq War was about 4,700 U.S. troops, and—the ranges are quite wide—anywhere from 200,000 to 600,000 Iraqis were killed there. Gaza, which is unfolding recently, is relatively small, as horrific as it might be. About 1,400 Israelis between the initial attack and the subsequent war, about 46,000 Palestinians. So those are pretty significant numbers.

Wars drag on sometimes for a long time. But here’s a figure that might make it more real: 170 million people are now displaced by violence, by war, either civil war or interstate war.

That’s a fairly substantial fraction of the global population living outside of their home as a result of conflict. These aren’t the actual combatants. These aren’t the soldiers or the militia groups or the rebels who are actually fighting. These are innocent people, who are caught up in the violence that’s surrounding them and have been forced to flee from their homes, their communities, their support networks, and have moved across the border to another country.

So it gives you a sense of what goes on, right? Lives are disrupted, people are forced to leave their homelands, in a serious, sometimes long-standing way.

Lindsay: You have been a scholar of international relations for more than four decades, and are very well known for your work on international relations and conflict and peace.

Give us a little bit of your background, help our listeners kind of get a sense for who you are. Why are you interested in matters of war and peace?

David: I was politically socialized at the tail end of the Vietnam War. I am still young enough to say that I missed the draft by a couple of years.

But when I was in high school, the Vietnam War was still going on, and I got very involved in the anti-war demonstrations. That planted the seed of interest, but for some reason I’ve always been fascinated, perplexed, disturbed by large scale conflict. So, there was no doubt, as an undergraduate, I was going to major in international relations and study war. I went to graduate school to study nonproliferation, which was my interest at the time. Discovered there was lots of other things going on, so I wandered around through a lot of other topics. But this has been a sort of a pillar of my research, as an academic, for obviously quite some time.

Why are people drawn to particular topics? Sometimes hard to know, right? But certainly, growing up during the Vietnam War, and sort of coming of age and developing a political sensibility in not only the conflict that was unfolding, but the dissent, the protests, the riots in the United States, as we as a society struggled to figure out what we should be doing where around the world, made a pretty dramatic impression on me.

Lindsay: Yeah, that’s interesting. I think about scholars who are my age who were really shaped by September 11th and went on to do work on international terrorism and things like that.

In a recent paper that you wrote for IGCC, you unpack the different ways that academics try to explain why wars happen. You say that it’s not so much that states are looking for victory over something, to gain something, you know, like land, but that it’s actually, when we see a war, what that means is that the warring parties have failed to negotiate something and that war is kind of the last resort when all the other options have been foreclosed.

Can you talk us through, why is this way of looking at war—the way that you describe in your paper—why is that important? And is it mutually exclusive from thinking about war as about victory and wanting something?

David: Yeah, we’ve had a change over the years in how we think about the origins of conflict.

Used to be what we can call traditional theory. It was very intuitive that war was a result of desire, right? You had countries, in [the] case of civil war groups, [who] would have some objectives they wanted to accomplish. And the motive, in turn, was then the explanation. Think about it in very simple terms alright? World War II, Hitler has desire for territorial expansion to dominate areas in Eastern Europe, to sort of enlarge and expand the German Empire. And then we’d look at that war and say, well, Hitler caused it, right? That it was his motive, his desire that caused the war.

How we now think about war, though, is, as you said, sort of a failure, a failure of bargaining, right? It is still the case that you have to have some issue in dispute. Countries disagree about the division of territory, who should control what or even who’s going to control the central government, in the case of a civil war or something like that. So that conflict of interest still lies there. But there are conflicts of interest all over the place, and war is actually pretty rare, right? So then, why is it that some conflicts of interest either don’t escalate into war, or are in fact solved? And why do, in those rare cases, we turn to violence on a large scale to try and resolve our differences? Because war is costly, right? As we said at the beginning, millions of people sometimes get killed.

So in the old traditional way, we used to sort of look at the victor and say, well, the victor won. The victor got what it wanted and maybe it was willing to pay the price to do that. But the loser lost, and still paid the price. And so even if, in most cases, wars get fought to a stalemate, or some compromise that falls short of the ambition. So why couldn’t they have agreed to that compromise before slaughtering large numbers of people, disrupting lives, forcing refugees to flee and so on and so forth.

So now we want to think about war as this failure, and say what are the conditions under which you cannot reach an agreement? And two central points come out of the new research. One is that one or both sides have what we call private information with incentives to misrepresent. I know something about myself, my battle plan, my resolve, my capabilities, that I can’t share with you in advance of the actual conflict.

A very good example is the Persian Gulf War from 1991. So the United States arrays its troops in Saudi Arabia with the intent of pushing Iraq out of Kuwait. Iraq invades Kuwait in the summer of 1990, occupy the country. The United States develops and brings 600,000 troops to Saudi Arabia, and the idea is we’re going to force the Iraqi military out of Kuwait. We develop a battle plan wherein we’re deploying the bulk of our forces on the Saudi/Kuwaiti border and carry out an extensive bombing campaign that destroys Iraq’s communication structure. In the week before the actual ground fight, we shift the troops to the left, away from Kuwait into Saudi Arabia, the Iraqi border. And then, the U.S. battle plan was the so-called left hook, where the tanks, military, raced up into Saudi Arabia and then turned and attacked the Iraqi forces from the side. They were unprepared for that. Many of the Iraqi tanks were actually dug into the bunkers, facing south, expecting the U.S. and allied troops to come into their barrels, right? So they got decimated.

Now, we knew we were going to win. The Iraqis held out some hope that maybe they’d be able to defend themselves from the frontal assault that they were anticipating. We could have sat down at the negotiating table and said, “We know we’re going to win because we’re going to do this left hook, right, and we’re going to catch you by surprise and we’re going to destroy your forces.” But had we done that, we would have lost the element of surprise, right? So that’s a clear case of where we knew something about ourselves. We prepared, but we couldn’t actually share that with the Iraqis to let them know that they were going to lose without a doubt, and therefore should give up before we actually fight.

So, we can see these information problems leading to failed negotiations. The other way in which bargains fail, and we understand them to fail, is as problems of credible commitment. So in a problem of credible commitment, I cannot trust you to implement the agreement that we would reach without fighting.

Why is that? Typically, something will happen during the war or as a condition for peace that leaves one side stronger, and in a position to overturn the agreement that might have existed. So, a really good example of that, Barbara Walter, one of our colleagues here at UCSD, her first book brilliantly showed that as a condition for ending a civil war, rebel groups have to disband and lay down their weapons.

So, imagine you reach an agreement that maybe the rebel group gets a certain measure of autonomy in a region of the country. They’ve come to an agreement that leaves them both better off than continuing to fight. But now the rebel group is disarmed. The fear is that the state will take advantage of that, and overturn the agreement and now destroy the rebels after they’ve given up their weapons. So, the rebels can’t trust the government to actually implement the agreement that they’ve reached at the bargaining table. So, as a result, the rebels don’t lay down their arms and the war continues, because they can’t trust one another to actually abide by the terms. The way out of that is either victory by one side, which Barb Walter finds that that’s the most typical outcome of a civil war, or some form of third party enforcement to ensure that the parties actually honor the agreement once it’s reached.

So in this way, we’ve sort of reconceptualized war as not just a motive. Motive is important, right? There has to be something you disagree about. But what are the conditions that prevent us from reaching agreements in an efficient way beforehand?

Lindsay: It’s interesting, I mean, thinking about the war, one of the wars that’s on our minds a lot, looking ahead to the third anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it’s hard to envision, you know, some negotiated pre-war settlement, like Ukraine agreeing to give up some of its territory to Russia in advance, anticipating how costly a war of attrition would be.

It’s just hard to like, imagine that happening.

David: Yeah, so look, one of the things that’s hardest to know in advance, is the issue of resolve. In the case of Ukraine, it was very hard for anyone in advance to know just how committed the Ukrainians were to keeping their country democratic and Western-oriented, and how committed they were to actually fighting and what their capabilities were.

Making it even more difficult to anticipate was, what was the West, the United States and Europe, going to do to back Ukraine, and just how much support they would have. So, in advance of the war, it’s very hard to estimate all of that.

And think about what private information with incentives to misrepresent actually means. So Russia doesn’t know how committed Ukraine would be. So they start what they anticipate to be a very quick war, they’re going to go in and decapitate the Ukrainian government, and take over the country. They couldn’t know how resolved the Ukrainians were in advance.

Lindsay: Is there a great example of a war that should have happened, but didn’t, because it was successfully negotiated?

David: Most conflicts of interest, most of the time, don’t result in war, right? Use that as your baseline. Most of the time we are able to reach some sort of agreement. An example I’d like to point to is the United States and Great Britain, in the 19th century, have lots of contested border regions, including the Oregon Territory. And both sides are sort of itching for a fight on how to divide the Oregon Territory, which spanned what is now Canada and Oregon, the state of Washington, and so on.

So both sides were preparing for war over this. But they successfully sat down at the negotiating table and compromised, and basically split the Oregon Territory in two, half for Canada and half for the United States. So just one example how, even in a case where, you know, sides are committed to territory and it’s very important, that at the end of the day, were able to reach an agreement.

Lindsay: You write about sort of the irrationality of going to war, given how costly wars are. But not everyone bears the costs directly, right? So there’s a suggestion that I guess the cost would dissuade whoever it is that chooses to go to war from going to war. But what if the people who choose to go to war don’t really bear the costs?

David: Right. The country as a whole bears the costs. Lives lost, wealth dissipated. In war, you’re essentially burning money at the extreme.

So there’s a lot of work, building on this sort of new understanding of war, of what about leaders, who may be politically unpopular or at risk of losing office? Could they have an incentive to start a war? The research shows that Yes, sometimes they do that. If they win, they survive. If they lose, they die. So it’s a risky gamble. And sometimes leaders may choose, because they themselves don’t bear the full cost of fighting, and they’re going to hope for a positive outcome for their country, which will reinforce their popularity or their ability to hold on to office. So leaders may take the risk. But again, the costs are borne by the country as a whole. And especially if the leader brings the country into a war that they lose, they will almost certainly be displaced from office and most typically die.

Lindsay: I do want to ask you a question about Israel and Palestine, and that conflict, as we’re talking about war, but thinking about political violence more broadly. I’m curious, with all of these ideas in mind, how you explain the most recent phase of this conflict in Israel and Palestine.

It goes back a long way obviously, but most recently we think about Hamas’ attack on October 7th, which has been followed by a pretty brutal onslaught, some of the mortality which you referenced in your introduction. You have also written recently for IGCC about this. It’s easy to kind of view Hamas’s actions as self-defeating, but you also suggest that there might be a logic to this decision [for Hamas to launch the attack against Israel].

I’m wondering if you can just walk us through this line of thinking.

David: The Arab-Israeli conflict, going on now close to 75 years, has always, at one level, been a problem of credible commitment, where Israel doesn’t trust the Palestinians to honor any agreement they might be able to reach, and the Palestinians don’t trust Israel, particularly given its military superiority, to honor any agreement they might reach on the ground.

And the current ongoing conflict is also now sustained by that same problem. Israel doesn’t trust Hamas to honor any agreement they might be able to reach on the ground, and Hamas doesn’t trust Israel.

Now the immediate precipitating factors for the conflict have much more to do with this private information that we’ve been talking about earlier. What actually sort of caused the attack on October, Hamas had built up its military capabilities, which Israel didn’t know about, or to the extent they knew about it, they refused to believe. We now know, of course, that Israeli intelligence agencies had uncovered the plan that Hamas used, and it made it up to several rungs in the Israeli bureaucracy, but then was ignored because it seemed implausible. In some ways, Hamas had to attack to show its capabilities, in order to sort of push the Israelis to the bargaining table, they had to show that they had the capacity to hurt Israel. And they could say, “Oh, look, we have this new great operative capability, and we know how to attack and impose harm on Israeli citizens, so you should compromise.” But they couldn’t reveal that plan without initiating its impact, right? So the only way they could prove to Israel that they were capable and Israel should go to the bargaining table is by actually launching the attack, right? So that’s the precipitating factor.

But with Israel’s response, which was fully expected, we’re now in this problem of credible commitment where, yeah, there’s agreements. We know sort of what the ceasefire is starting to look like, right? But the question is whether it will hold. And can the two sides actually trust each other to implement the agreement?

But there was a larger strategy Hamas was pursuing, not just trying to demonstrate its strength to Israel, but think of it as a sort of a “violent boomerang,” is what I called it in the post for IGCC. Hamas knew that Israel would respond, and , at least in the popular view, respond disproportionately.

That brought to global attention the plight of the Palestinians. Think about the reactions that unfolded across college campuses in the spring of 2024. It mobilized public opinion, in support of Palestinians and against Israel. That changes the pressure on the United States and European countries, when they’re dealing with Israel and able to put some pressure on Israel to come to the negotiating table.

My personal view is Netanyahu would not have agreed to the ceasefire without pressure from outside. And that pressure from outside came from the United States and other countries that were being pressed by their citizens, who were despairing of the violence and deaths that were happening in Gaza.

So Hamas is not just trying to put pressure on Israel, but it’s trying to bring the issues to global attention, and expecting Israel to respond forcefully, knowing that that would mobilize communities outside of Israel to put pressure on their governments to put pressure on Israel.

Lindsay: You write in your paradigm paper that if the initiation of war is understood as a bargaining failure, then wars can end when these issues are resolved, leading to a mutually acceptable agreement.

What does this concept of war tell us about some of the most kind of potent conflicts that we are in the midst of today, you know, whether it’s Israel/Gaza, or Ukraine, or Sudan or any other war? And I’m curious what it might tell us, too, about some of the conflicts that many are worried about or anticipating. Like here at IGCC, we think a lot about China, and we have done podcast episodes asking the question, is China going to invade Taiwan? China certainly talks about it the way that Russia has talked about the territorial history of Ukraine as an extension of Russia.

How does this concept, what does it tell us about how these wars might end and how they might be prevented?

David: Well, let’s think about ending or preventing war in the first place.

Wars of private information, we think, tend to end pretty quickly. Once the war starts, you’ve revealed your battle plan or you’ve demonstrated your resolve and both sides can update their beliefs and move towards negotiations, hopefully relatively quickly. Again, think of the Persian Gulf War and the left hook. Once we demonstrated the military strategy and defeated the Iraqi army, war was over in a hundred hours. A couple of days. So the information is revealed, the parties update and say, okay, we’re going to lose. And the United States says we’re not going to push this to the ultimate conclusion, we’re not going to try and overthrow Saddam Hussein in 1991. So, we’ll agree that Kuwait’s liberated, Iraqi forces leave, and we go back to the status quo.

Even within that though, wars of information can be potentially avoided and/or brought to an earlier conclusion through mediation. Some interesting studies show that a good mediator can extract the information from both sides and be able to help the parties reveal the information that they have so that they can come to a compromise agreement, either before the conflict starts or relatively quickly, right? We’re still working on that. Lots of questions to be answered, but this is the big hope in those cases, that we can reduce the propensity for war by eliciting greater information from both parties.

And this is a main pillar of the explanation for why democratic countries tend not to fight one another, is that they’re more transparent, they’re more open. So, it’s not that there are no conflicts of interest between democratic countries, but we’re able to avoid conflict because the transparency of the political systems allow[s] information to be shared and used to sort of help resolve differences before they get too acute.

Problems of credible commitment are a little bit harder to resolve here. I said before that they tend to end in one of two ways, which is either total victory by one side, or some kind of third-party enforcement. That’s true for civil wars very clearly, true for interstate wars, as well. Why they go to total victory is, if I can’t trust you to honor the agreement, I have to reduce your capacity to fight in the future. So not only do I have to sort of win immediately on the battlefield, but I have to destroy your capacity. And so, uh, you fight to the end, where for at least a foreseeable future, I cannot imagine that you would have the capability to restart the war, and both sides are trying to do that to each other, and so you get these very long wars of attrition.

The other way they end is by third party enforcement, where the agreement is reached and then some third party guarantees the agreement. The solution that’s emerging for many of these is UN and other international organizations undertaking peacekeeping operations. There have been 70-some odd peacekeeping operations since the UN was created. There’s 11 active ones now. And it can be everything from sort of policing the border to actually placing troops in between the warring parties to separate them. So that’s emerging as a solution to these wars of credible commitment.

Many of them go through international organizations, the UN or the organization of African states. But there’s also a role for individual countries, right? The United States sometimes has been able to guarantee peace agreements in civil wars, in particular. So that’s the great hope there. Those are two strategies that we believe have some effect in reducing the conflicts and ending them more quickly than they might otherwise.

In terms of U.S. and China, the competition is now unfolding. Look, war is always a possibility. The tensions between the United States and China are real, right? There’s conflicts of interest there. The big issue is what is the resolve on both sides, particularly if you want to think about Taiwan or the South China Sea. How committed is China to obtaining control, sovereignty over Taiwan? How much blood and treasure are they willing to spill in order to reclaim the island?

Flip the question around: what’s the U.S. commitment to Taiwan? We have a policy of strategic ambiguity, which we hope would deter China from attempting to retake Taiwan by force. But that ambiguity cuts both ways, right? It can deter, but it can also lead China to say, “Well, the United States isn’t all that serious.” We’re cheap talk. We’re just saying we have a commitment without drawing a clear line where China, if you do this, then war will happen. So, the big risk of war with China probably comes from these informational problems, and questions of resolve, most importantly.

Ken Waltz wrote a very famous book called Theory of International Politics. It’s really a dissection of the Cold War and the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. And he made the case there that, in a bipolar world where there are two superpowers, two nuclear-armed superpowers, they paid very close attention to each other. They tried to know everything they could know about the other, and that actually reduced the risks of conflict between the two superpowers, relative to the multipolar era where there were lots of great powers and shifting alliances and so on. That was a very murky system.

Bipolarity is a little bit clearer. They’re two big countries who can destroy each other, and they’re going to spend a lot of energy trying to infer as much as they can about the other’s intent, its resolve, its capabilities, and so on. So, you know, the United States and China are paying now very close attention to one another, and doing everything they can to learn about the other’s intentions and to signal what they know, and perhaps what they’re willing to fight about.

Lindsay: That’s why my boss [Tai Ming Cheung] is so busy.

David: Exactly.

Lindsay: I was struck reading your paper at how analogous all the stuff that you describe is to just our own lives, you know, and the way that we interact with people, you know, the way that we fight, the way we hide our intentions, how messy it is, but how, how incredibly analogous it is. So if anyone thinks that they can’t understand conflict at a global level, they probably can more than they think. Because these dynamics play out in our own lives, too.

But on the one hand, in the paper, you know, you’re talking about the sort of costs and benefits and this cold, dispassionate calculation, and we all know that people don’t work that way, of course. People might resort or be motivated towards political violence, towards war, civil war, even terrorism for lots of, like squishy things, you know, like, because they feel humiliated, because they think it’s moral, because it’s exciting, because of identity things that are really hard to measure.

It’s so kind of messy, and I think of it almost like a bowl of spaghetti noodles where it’s hard to disentangle, you know, what is the key driver. And having studied it, you know, for so long and so extensively, I’m curious, given how messy it can be, how hard it is to know, as an outsider, what’s really going on. You mentioned the role of outside mediators, and of course the U.S. has played that role all over the world for a long time. Given the messiness, can outsiders play a helpful role in that? Like, what is that role, given how giant the information asymmetry can be?

David: It is messy. One of the beauties of the bargaining approach to war that I’ve been talking about is that it’s actually very general. You’re right that it applies to our daily lives. In undergraduate courses, I always walk them through the example of a conflict with their roommates. It’s the same. Who’s going to take out the garbage in his shared apartment, right? You know, it’s a conflict. Sometimes you have to break up with your roommate because you can’t resolve those sorts of things. So the same ideas carry over from civil wars to interstate wars to rebellions, whatever it might be.

And they are messy. Emotions, identity, all come into play here. One of the great frontiers for research continuing in this direction is to try and understand the role that irrationality, emotions, quick decision making, plays in pushing countries, groups over into actual conflict. Trying to integrate some of the psychological perspectives with the bargaining model. That is the research frontier, as it exists in the field now.

But there’s a special quality to war. Daniel Kahneman’s famous book, [Thinking, Fast and Slow], distinguishes between our reptilian part of our brain, right, where we respond very quickly to assaults, to conflicts, where we respond very emotionally and very quickly without always thinking through the consequences. But there’s the “thinking slow” part. When things really matter, you’re going to sit down and think carefully about the consequences and try and anticipate the reactions of others to your actions and so on. So yeah, you might get in a screaming match with your roommate or partner, but you’re much less likely to react emotionally and quickly, in my view, to going to war with another country where maybe you’re going to kill 30 million people.

To say that, you know, that solves that sort of psychological dimension to decision making? No. There’s always the chance that somebody with their finger on a button can override rationality and careful decision making. But the incredible costs that we talked about at the beginning do give us some reason to hope, tha, emotions don’t completely rule our thoughts when it comes to big decisions of war and peace.

Lindsay: Do you think that the election of Donald Trump and the shifting global balance of power makes wars more likely in the future?

David: That’s a really hard question to answer. Trump has introduced a great deal of uncertainty into American foreign policy, sometimes described as the chaos president. He appears to believe that uncertainty, his unpredictability, will deter challenges to the United States. He sort of embraced what, surrounding Richard Nixon, was originally called the “madman” theory of diplomacy. “You don’t know what I’m going to do, so you better be careful,” is the idea there.

President Trump seems to be sort of engaged in a similar kind of exercise, but as I said earlier, unpredictability, uncertainty cuts both ways. Yes, it can deter, but it can also leave the opponent questioning your resolve. Will we defend Taiwan? Will we engage with Ukraine? Will we actually turn Gaza into the Riviera of the Mediterranean? What are we to infer about American intentions when uncertainty is intentionally increased? I think it’s very hard to make a prediction about what will happen in the next few years under President Trump because this uncertainty is so uncertain, and its consequences are so hard to predict. I would hope that the administration will recognize that uncertainty cuts both ways, it can deter, but it can also lead your opponents to make mistakes, and challenge you when they otherwise would not.

Lindsay: David Lake, thank you for being with us on Talking Policy.

David: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.